I’m still thinking about the Macroblog post last week on Inflation Confusion, which said in part:

“When food prices rise or oil prices rise, people are right to feel in some sense worse off, because they are. And if you are tempted to call that “inflation,” I understand. But for policy purposes, the distinction between cost of living increases and inflation as a deterioration in the generalized purchasing power of money is critical.”

If that distinction is really so critical, shouldn’t policymakers utilize inflation metrics which explicitly focus on prices other than consumer prices? If in fact monetary policy wants to focus on something other than ensuring a stable cost of living for the median consumer, why is the public emphasis of policymakers always on the CPI? Furthermore, why did these policymakers explicitly ignore huge warning flags such as house prices grossly above historical norms (2005-2007), stock market valuations grossly above historical norms (1998-2001), and rapid expansion in money and credit at rates vastly greater than underlying GDP (1982-2008)? Policymakers who actually cared about monetary inflation should’ve taken away the punch bowl a lot sooner in each instance. The fact that they did not gives the impression that policymakers were in fact focusing only on the cost of living, ignoring the distinction claimed above. (The other commenters at that post also critiqued this distinction.)

Now, the current inflation angst may also be partly about displaced budget frustrations. For many groups of people — the unemployed, the underemployed, those re-employed at lower wages, workers facing state and federal wage freezes and endless, inevitable budget cuts, and retirees whose savings/CD income has been crushed by low interest rates while Social Security hasn’t budged, to name a few — there are plenty of reasons to be worried that a deflating income won’t stretch to meet inflating goods prices… especially when debts have to be repaid as well. So even if the goods prices aren’t inflating much, the income deflation and debt burdens are bad enough.

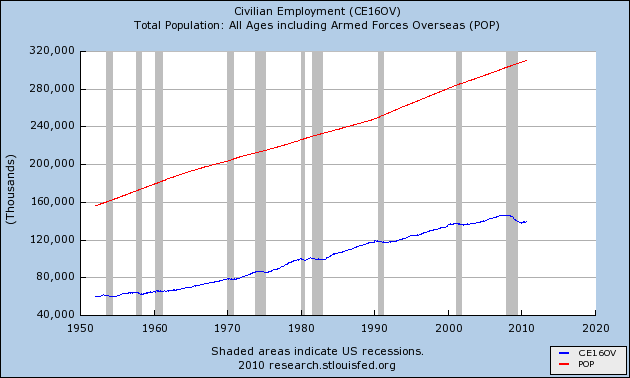

At the end of the day, however, the real problem in restoring prosperity isn’t about inflation, it’s that we need to restructure both the economy and the government. We need to get more people producing genuine goods and services, things that really make the nation a better place to live in. We need to shift workers away from wasteful and even counterproductive activities. And we need to face the reality that for decades to come, there are going to be more retirees and probably fewer workers to provide for them all. We need political leaders willing to roll up their sleeves and do some serious work, not simply grandstand for narrow constituencies while exempting themselves from the laws they write for the rest of us.

But, going back to the Inflation Confusion post, we see no evidence of an Activist approach to running the Federal Reserve. Instead, we see this quote from Atlanta Fed president Dennis Lockhart:

Monetary policy is a blunt instrument without the capacity to systematically influence prices in targeted markets.

The good leader appears to forget that the Federal Reserve, and the government more generally, have all manner of policy tools at their disposal, and some of these are quite sharp. For example, the Federal Reserve has a tremendous amount of regulatory discretion. Used judiciously, this tool could not only clean up terrible financial institutions, it could “systematically influence prices in targeted markets”. As just one example: had the Federal Reserve bothered to enforce reasonable lending standards in 2004-2007, they certainly could have “systematically influenced prices in targeted markets”, namely the price of housing in the bubble states, where the most egregiously bad lending took place. That would have been painful at the time, since no one wants to take away the punch bowl and be blamed for starting a recession. But such a policy would have prevented the far greater economic pain we have suffered since 2007, including most recently the current inflation problem.

Is there a similar policy tool, which might inflict some economic pain now, but which will prevent far greater pain down the road? I think there is! Here are a few policies we could pursue that might hurt now, but would clearly fix things that are out of balance, and should help us later:

First, we should persuade all trading partners to float their exchange rates over the next 2 years. Keeping the dollar misaligned relative to our partners subsidizes their economic development at our expense. But we cannot afford to subsidize the economic development of the rest of the world for much longer. Another problem with misaligned exchange rates is that capital flows out of the U.S., while debt remains. This is not stable and the imbalance needs to be unwound. The current monetary inflation is a step in the right direction, but more needs to be done to increase savings rates and reduce debt-to-money-supply ratios within the U.S.

Second, we need to return to policies which encourage genuinely productive investment and reduce the national addiction to debt marketed as “credit”. At the moment we have a tremendous amount of malinvestment… we have a horrifically unproductive health care sector… we have a financial sector which appears to have been a net drag on the economy for a decade… and we have too much debt relative to tangible value. In fact, to rewrite the classic line by Churchill, it may be that we have reached a point where “never in human history have so many people owed too much, to too few“.Third, we need to bring the national and state government budgets back into balance at a level, relative to GDP, which is consistent with the middle of the historical range. As with any budget pruning exercise, a lot of worthwhile, very reasonable activities will have to be cut back or terminated in order to allow higher-priority, more worthwhile activities to continue. No major budget category should be spared.

It’s ridiculous that we spend more on defense than the rest of the world combined. And we spend far too much relative to our GDP. While our soldiers deserve our support when we send them into harm’s way, perhaps we are putting too many in harm’s way, for too little gain? How ironic would it be if, in Egypt, the protesters achieve more in a month than the entire U.S. military (with trillions of dollars) achieved in a decade in Afghanistan? But perhaps more importantly, it’s impossible to claim that the entire defense budget is “essential”, so let’s prune the nonessentials. And ridicule anyone who claims that the whole budget is essential to national survival. We will have to accept some consequences, but we have to live within limits again.

It’s even more ridiculous that we spend far more on health care (as a share of GDP) than any other major nation, and yet we get worse outcomes. Social security needs to be updated for modern life expectancies, but it could include another lower-payout “early option” for those who are forced into medical retirement before the median age. And it could include a phaseout for those who have millions of dollars in assets, hundreds of thousands in income, and clearly don’t need welfare for the elderly.

And finally, a huge swathe of “discretionary” spending is in fact discretionary. Some of it is prudent investment, so it’s unfortunate that Congress is tackling this last part first, because I think it’s the hardest to fix. There are too many details, and in proportion I think there’s less fat in this part of the budget, so I fear they’ll never get to the health care sector where the bulk of the budget problem lies.

Looking at these 3 policy approaches, what role could the Federal Reserve play?

First, the Fed could stop subsidizing congressional overspending. As has been said, the national debt isn’t created by the Fed, it’s created by Congress. But Congress wouldn’t be “enabled” to borrow so much, if the Federal Reserve were to stop monetizing it — and especially not if the Fed began to raise interest rates to fight inflation, thus raising the cost to Congress of being in debt. We should all be horribly ashamed that our great nation has gone from “tax and spend” (which I recall was a really bad thing in the 1980s!) to “borrow and spend”, and now we’ve reached “print and spend” within just 30 years. There’s a natural size for the government, above which bad things happen, and everyone should quit trying to make the government bigger than that size. We should be debating what fits inside the government’s slice of the pie, and working to grow the pie for everyone — not borrowing to make the government’s slice bigger now at the expense of painful repayments later.

Second, the Federal Reserve could cease tacitly supporting financial fraud, clean up the banking sector, and bring to light as many cases as possible where bankers lent foolishly (or even criminally) and are now broke. Does the Federal Reserve represent the financial industry as a whole, or just a few of the most troubled banks? If the former, then among the latter, those responsible for the destruction of national and shareholder wealth need to face punishment, not be silently rewarded. We need to get to the same “never again” mindset that policymakers adopted in the late 1930s, and institutionalize that mindset so the reforms will stick for as long as possible. The banks which get with the program and clean up their business could be rewarded… and if necessary, the others could be cleaned up through aggressive regulation, if the Fed learned how to lift its little finger. It’s time to recognize that the system is more than a collection of parts, and indeed that those parts which are incorrigibly broken must be replaced.

Third, the Federal Reserve needs to start lobbying for, and implementing, systemic financial limits. To reduce debt levels relative to GDP, a good start would be to reduce financial leverage limits. For every borrower there is a lender, and there are currently too many lenders willing to lend too much relative to GDP. At the moment the marginal utility of debt appears to be quite low, particularly in the housing sector, so a reduction in bank leverage might not have as much of an impact as it would if this policy were implemented in the depths of a recession or during a raging credit-starved economic boom. This could be a golden opportunity, in fact.

The goal must be to get to sustainable economic growth, not “growth at any cost”, and certainly not “the illusion of growth because we neglect to measure inflation adequately”…

Furthermore, if you need to Send money to Colombia from the United States, you can do it in-store, online, or using the MoneyGram mobile app, which is available on the App Store and Google Play.